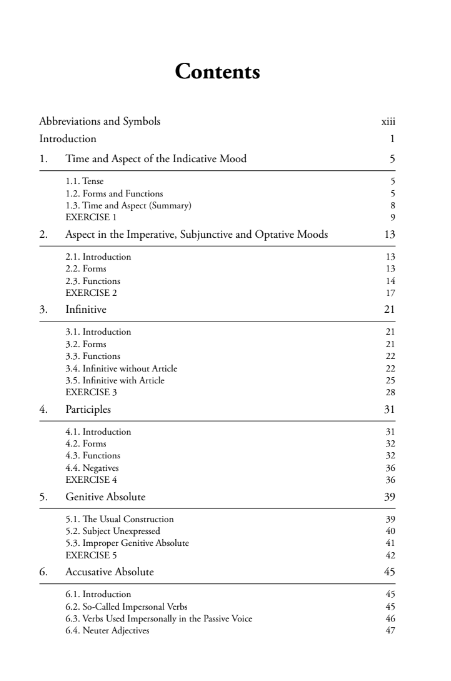

Mục lục

ToggleIntroduction

This series of Lessons and Exercises is intended for students who have already covered all or most of an introductory course in the ancient Greek language. It aims to broaden and deepen students’ understanding of the main grammatical constructions of Greek. Further attention is given to grammatical forms only to the extent necessary to illustrate their functions. With one exception, all Greek passages in the Lessons and Exercises (including English to Greek translation) are direct quotations from Greek authors. Some quotations are modified by the omission of a few words (marked by ellipses) for the sake of brevity, but without affecting the grammatical structure. In Lesson 19 on Conditions, brief model sentences have been employed to demonstrate more clearly the variety of conditional sentences.

In the Lessons, all Greek passages are translated into literal but reasonably idiomatic English. For the most part, passages in both the Lessons and the Exercises are drawn from main genres of the classical period (fifth to fourth centuries BCE)—tragedy, comedy, historiography (together with biography), oratory and philosophy. Non-dramatic lyric is not often used, since it is more difficult to understand a single sentence out of context in this genre. Didactic poetry (Hesiod) also appears seldom. Homer receives attention at particular points, mainly Homeric conditions (Lesson 20) and Homeric similes (Lesson 28 on clauses of comparison). In general, the focus is on the classical Attic dialect. Where Epic or Ionic forms occur, they are explained if necessary. Occasionally there are references forward to the Hellenistic period.

The first few Lessons have an emphasis on Time and Aspect in the Greek verbal system. After the Moods of the finite verb in Lessons 1 and 2, Infinitives and Participles are treated in Lessons 3 and 4. The absolute constructions of the Participles in the Genitive and Accusative Cases follow in Lessons 5 and 6. The verbal adjectives ending in -τος, -τη, -τον are treated in Lesson 7, and those ending in -τέος, -τέα, -τέον in Lesson 8. Lesson 9 is primarily concerned with the use of the Middle Voice in the classical period. Lesson 10 deals with commands and Lesson 11 with wishes. These two Lessons expand the concise treatment of Imperative, Subjunctive and Optative Moods in Main clauses in Lesson 2. In addition to the most basic constructions, Lessons 10 and 11 present the variety of ways in which commands and wishes may be expressed. These two Lessons also cover the subordinate constructions for reported commands and reported wishes.

Lesson 12 provides a brief and basic presentation of directly quoted statements. This leads on to the range of subordinate constructions, which begins with reported statements in Lessons 13 and 14, and extends to Lesson 35. This sequence is interrupted at two points. Lesson 17 on questions is followed by Lesson 18 on reported questions. Lesson 21 on subordinate clauses in reported discourse is placed intentionally in the midst of the sequence of subordinate constructions.

Discussion of the Cases has been deliberately placed late in the series at Lessons 36 to 41. By this stage, students will be better prepared to analyse the Case usage with which they are now familiar. For the classical period, the consideration of prepositions in Lesson 42 naturally follows the treatment of the Cases. Lesson 43 on correlative clauses has numerous links with adjectival and adverbial constructions in previous Lessons. Finally, Lesson 44 deals with exclamations.

The majority of the Exercises comprise several passages for translation from Greek to English and one or more passages (depending on length) for translation from English to Greek. It is intended that students should use the full and most recent edition of A Greek–English Lexicon originally compiled by H. G. Liddell and R. Scott. Alternatively, The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek, originally compiled by F. Montanari for Italian readers, is now available with American-English spellings (see Bibliography for both dictionaries). However, to save time for students, some vocabulary is provided for specific passages in each of the Exercises. Exercises 7 to 9 and Exercises 36 to 42 involve translation from Greek to English only, but do require brief analytical comment. Exercise 20 on Homeric conditions involves translation from Greek to English only, but requires no further comment. Alternative Exercises (A and B) are provided for Lessons 34, 35 and 42. Exercises are of approximately equal length.

Accent marks indicate how a pitch accent was probably pronounced in Classical Greek. No separate Exercises are provided for this purpose. But the books of Allen (1987) and Probert (2003) are recommended.

The table near the end of Lesson 1 and the accompanying list of Tenses largely correspond to those of the Joint Committee on Grammatical Terminology (1911) as modified by Masterman (1962). Masterman (1962, p. 72) began his article with the following words:

It is over fifty years now since the formation of the Joint Committee on Grammatical Terminology, and the presentation of its Report; and it seems to be high time that teachers of languages considered, first, how successful they have been in carrying out its recommendations, and secondly, what modifications are called for in the light of more recent knowledge.

Since Masterman’s article was published, over 50 more years have passed, and it seems high time that a new intermediate Greek language textbook be made available. The grammars of Ancient Greek by Goodwin (1889) and Smyth (1956) remain the most convenient in English, despite their age.

LESSON 1

Time and Aspect of the Indicative Mood

1.1. Tense

Tense may be regarded as the combination of the Time and Aspect of a Greek verb. In classical usage, there are three Times—Present, Past, Future—and three Aspects—Imperfect, Perfect, Aorist.

The main functions of the Aspects are as follows:

- Imperfect expresses continuous or repeated action.

- Perfect expresses completed action or the state resulting from completed action.

- Aorist expresses momentary action or sums up a whole period as a single action.

- Aspect is not inherent in an action but expresses the point of view of the speaker or writer.

(Palmer regards ‘durative’ as an inadequate description of the function of the Imperfect Aspect and prefers to think of it as the ‘eye-witness aspect’.)

The combination of three Times and Aspects would give a theoretical nine Tenses. But Greek does not have separate forms for each of the nine theoretical possibilities.

1.2. Forms and Functions

By way of illustration, the first person singular forms of the Indicative Active are given in the following list. The Active Voice of παύειν is normally used transitively (i.e. with a direct Object).

1.2.1. Present Time

Present

παύω — I am stopping / I stop (repeatedly or regularly)

This Tense form is properly Present Imperfect. However, there is no separate form for Present Aorist. So παύω also covers the meaning ‘I stop’ (momentarily), and the Tense is usually called simply Present. The Aorist function of the Present is most obvious in the Historic Present usage, where a Present Indicative vividly expresses a past action.

Present Perfect

πέπαυκα — I have stopped

It is generally agreed that, at the earliest stage of its development, the Perfect Aspect expressed a state resulting from previous action. In the classical period, this is especially noticeable with the Present Perfect forms of certain verbs used with Present meaning, for example:

- οἶδα — ‘I have come to know’, hence ‘I know’

- ἕστηκα — ‘I have taken my stand’, hence ‘I am standing’

By the later classical period, the emphasis on completed action had become more prominent and new Perfect forms with this resultative force were invented. But this emphasis had declined again by the first century CE. The Present Perfect and the Past Aorist Indicatives became increasingly interchangeable during the first three centuries CE. By the fourth century CE, the Present Perfect had been superseded by the Present (replacing its stative force) and by the Past Aorist (replacing its resultative force).

1.2.2. Past Time

In the classical period, all three Past Tenses were marked by the augment ε and had endings different to the Present and Future Tenses. Verbs with an initial short vowel in the Present Tense (e.g. ἱκετεύω with short ι) regularly lengthened the vowel in Past Tenses (ἱκέτευον, ἱκέτευσα with long ι).

Past Imperfect

ἔπαυον — I was stopping, I used to stop

Past Perfect

ἐπεπαύκη — I had stopped

ᾔδη — I had come to know, (hence) I knew

εἱστήκη — I had stood, (hence) I was standing

Past Aorist

ἔπαυσα — I stopped

ἐπολέμησα — I fought

‘Stopping’ is by nature a momentary action. ‘Fighting’ a battle or a war is by nature a continuous action. In the following passage, neither the composition of the account of the Peloponnesian war nor the actual fighting of the war was a momentary action. But both actions are summed up by the complexive use of the Past Aorist Indicatives (ξυνέγραψε, ἐπολέμησαν).

Θουκυδίδης Ἀθηναῖος ξυνέγραψε τὸν πόλεμον τῶν Πελοποννησίων καὶ Ἀθηναίων, ὡς ἐπολέμησαν πρὸς ἀλλήλους … (Th. 1.1.1.)

Thucydides the Athenian wrote an account of the war of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, how they fought against each other …

1.2.3. Future Time

Future

παύσω — I shall stop (Aor. Aspect) / I shall be stopping (Imperf. Aspect)

There are not separate forms for Future Imperfect and Future Aorist. The Future is primarily Aoristic in function. Some scholars explain the Future Indicative as derived from an Aorist Subjunctive with a sigma suffix. παύσω is an ambivalent form:

- I shall stop (Future Indicative)

- I am to stop, let me stop (Aorist Subjunctive)

Palmer (1980) prefers to explain the Future as a desiderative Mood in origin. Alternatively, the Future could be regarded as an Intentive Aspect in function. (Cf. the other common English idiom for expressing futurity: ‘I am going to stop’.)

Future Perfect

πεπαύξω — I shall have stopped

πεπαυκὼς ἔσομαι — I shall have stopped (periphrastic, the usual form)

Actual forms of the Future Perfect Active are rare; they occur especially in two verbs that are regularly used in the Perfect with an Imperfect meaning:

- ἑστήξω — I shall have stood, (hence) I shall stand

- τεθνήξω — I shall have died, (hence) I shall be dead

Those verbs that form a regular Future Perfect Middle/Passive mostly prefer either a Middle or a Passive meaning. The Passive meaning is more common.

Emphatic reduplicated Futures such as δεδέξομαι ‘I shall certainly receive’ (Hom. Il. 5.238) constituted a model for the formation of Future Perfects from the Present Perfect base. Conversely, Future Perfect forms can sometimes be translated appropriately as emphatic Futures.

1.3. Time and Aspect (Summary)

Table: Time × Aspect

| Time | Imperfect Aspect | Perfect Aspect | Aorist Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | παύω — I am stopping | πέπαυκα — I have stopped | (παύω) — I stop |

| Past | ἔπαυον — I was stopping | ἐπεπαύκη — I had stopped | ἔπαυσα — I stopped |

| Future | (παύσω) — I shall be stopping | πεπαύξω / πεπαυκὼς ἔσομαι — I shall have stopped | παύσω — I shall stop |

In the Lessons and Exercises, the following terminology will be used for the Tenses of the Indicative Mood (cf. Masterman, 1962, 76):

- παύω — Present

- πέπαυκα — Present Perfect

- ἔπαυον — Past Imperfect

- ἐπεπαύκη — Past Perfect

- ἔπαυσα — Past Aorist

- παύσω — Future

- πεπαύξω — Future Perfect

- πεπαυκὼς ἔσομαι — Future Perfect (periphrastic)